May 29, 2025 Edition

By Emily Patrick

Steve Brown is a Greenville boy “born and bred.” Some may say his story starts when his father meets his mother in Chicago and “drags her to the North woods of Maine.” Years later, Steve would meet his wife in Connecticut and drag her to Lazy Tom Bog to see her first moose.

The theme of this story is the ties that bind generations. I called Steve to learn about Maine’s last log drive, but I uncover a family history of working in the North Maine woods that hearkens back to perhaps some of the first log drives, and a surprising revelation I wasn’t expecting.

Steve’s great-grandfather moved to Parkman from Prince Edward Island to make a go of it in the North Maine woods- and, turns out, he was pretty darn good at logging, eventually running his own company. Young Steve was fascinated by his grandfather’s tales about his father and how different logging was in those days- there were no mechanical saws, to start; everything was done by hand with cross-cut saws and axes.

Steve’s great-grandfather herded his horses and oxen from Parkman to Greenville Junction and floated them up past Seboomook to the Roach Pond area, where he would spend the entire winter skidding the logs in the snow; pre-automobile, this was the only way to do it. Steve’s grandfather would tell “crazy stories” of men spending entire winters in those isolated logging camps I’m sure far surpassed even the wildest tales that came out of the Long Branch.

Perhaps it was destiny Steve himself would work on the log drive, or perhaps it was just what young Greenville boys did in those days. He says the drive was “always there,” and it wasn’t until he went out and experienced other parts of the world, he realized his experience working the log drive in the Maine woods was at all unique.

Despite the bloodsuckers in the bogs and the mosquitos and black flies, the sweltering heat, always being soaked to the bone and the physicality of the job (Steve says if newbies survived the first season, they were “kind of” accepted), Steve “never saw it as work.” He says there were days he’d be out on the lake, drinking in the beauty all around him, and ask himself, “Are they really paying me to do this?” In fact, Brown says for everyone who survived their first drive, “It was their favorite job.” Everyone who worked on the drive, I mean really, really worked, loved it.

Steve was no exception; despite all the challenges, he just kept coming back for more. Altogether, Steve worked five summers on the drive. He says it was “pretty good money,” in those days, and helped him pay his way through college. Steve would eventually go on to teach, and then earn a degree in nursing. He worked in nursing for the next three decades until his retirement. Still, as he tells me some of his favorite stories of working the drive, his voice is youthful and his memory crisp and clear. As he describes growing up in Greenville and working summers in the woods, the lines between generations blur as common themes begin to emerge.

Steve would go to college in Boston in the winter and play a role. His peers would have been horrified to know Steve was white-water rafting on logs down the river in the summer like some kind of North Maine cowboy. In Massachusetts, Steve was a student, a serious intellectual, but when he’d return to his hometown in the summers, his “proper” Maine accent would return and, I can sense, his true self.

One such summer, Steve’s boss, Walter Gary, of whom Steve speaks with an almost otherworldly reverence, called him up and said, “Browny, there’s somebody out in front of me in a sailboat and he’s not moving.” This was a big problem, because Walter was towing about 10,000 cord of boom logs behind him on the Katahdin. Steve was commissioned to go out and reason with the stubborn boater, whom one could only assume was naïve or completely crazy.

Turns out, he was a little bit of both. When Steve tried to warn him about the imminent danger, he replied that, “Scott Paper doesn’t own the lake,” (that bit, I think, is up for debate, at least in those days) and “I have a lawyer.” Steve said something to the effect of, “Look, I don’t know about the law. But I do know who’s driving that boat and the physics and if you stay right here, we’ll be fishing you out of the water.”

The stubborn sailor eventually had an awakening when he realized the steamship Kate was full steam ahead and didn’t intend to change course. When he tried to start the engine of his small craft, however, he and Steve were both horrified when…it didn’t start. The belligerent boater escaped just in time.

Steve tells another story about saving a group of summer camp kids and their counselors from disaster on the lake. On a day the log drive guys deemed too choppy to go out on Moosehead, a small group of camp counselors thought it would be a perfectly fine day to take a bunch of minors out in canoes.

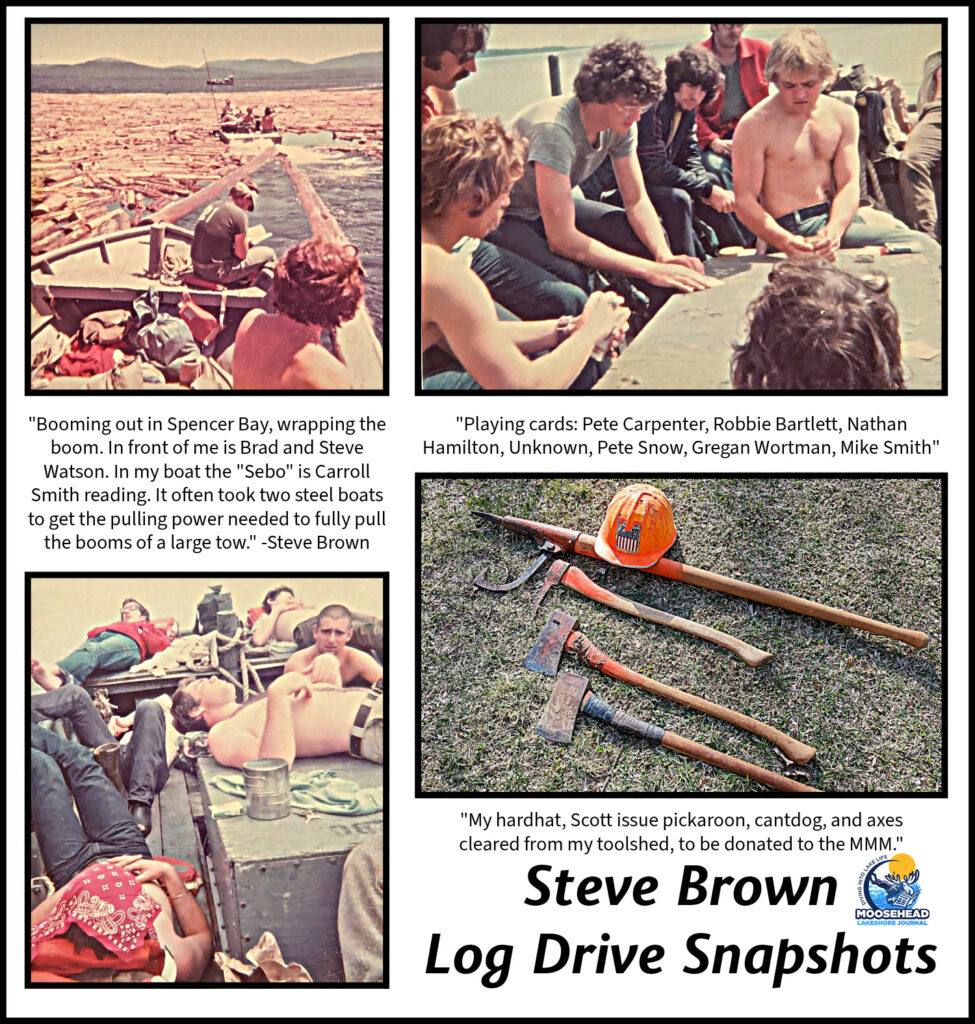

On another occasion, a bunch of Scott Paper “big leagues” came out to Spencer Bay in their finely-pressed suits and ties to watch Steve and his peers work. To be fair, Steve’s crew was “dressed up” too, donning hardhats for perhaps the first time that year to give the big bosses a semblance of safety on the jobsite. Steve says, “That summer, the lake was really low,” and Spencer Bay was especially tricky to navigate. When “Rocky” Rockwell hit a big rock and the best-dressed guy fell and “messed up” his suit, he was fuming. “Did you know where that rock was?”

The reply? “’Course I did, I hit it, didn’t I?”

If you grew up in the area, I’m sure parts of these stories resonate, whether you’re a Boomer or Gen X, Y or Z. As Steve tells other tales, I listen, enraptured, fascinated how closely I identify with much of what he’s saying simply because I grew up in Greenville. Most striking is that growing up here taught Steve to be tough and, by default, made him part of an exclusive club he had no idea he was part of.

Years later, Steve was working in the Dartmouth area. He was taking care of an elderly man, well into his nineties, dying of cancer. Steve spent some time talking with him, and the man said, “I was a logger.” Steve said, “Really? I used to kind of be a logger.” The old man looked at him indignantly. What could this “young” nurse know about the log drive? When Steve started slinging his log drive lingo, however, saying things only a man who had worked on the drive would know, the old man softened and told Steve incredible stories about working the drive on the Connecticut River, generations before Steve would work on Moosehead. He says, “That’s when I first realized, ‘Wow, maybe what I did was kind of different.’” He said, “[The log drive] had a big impact on my life….made you realize you could do just about anything…if you put your mind to it.”

Growing up in Greenville tends to have that effect, even through the generations. Steve’s experience tells a bigger story, though. Like so many of us in our youth, Steve took his unique experience for granted. Like Rocky and Chuck and others I’ve spoken with who worked the drive, Steve didn’t know that last big boom out of Spencer Bay would be the last. And, even if he did, he wouldn’t have realized the significance of it at the time.

Whether you grew up on the shores of Moosehead or in a far more exotic corner of the world, we all share a common human experience: we never know when it will be the last time we do anything, or the significance that might hold to future generations.

“We didn’t know it would be the last time,” Steve says, his voice trailing off. And, I wonder, would it really have made any difference? Is it really the last log drive that’s so significant? After having talked to several men on the last drive who treat it as an afterthought, I finally ask myself, am I chasing the wrong story? Perhaps it’s never the last time that’s so significant, but the countless moments before that makes the last time so very bittersweet.